The number of working-age Americans who make ends meet with disability benefits increased rapidly between 1996 and 2015. This increase also became an indicator of the divide between urban and rural America – in rural America, the disability benefit rates are almost twice as high as in urban areas. Earlier, a report in the Daily Yonder had also highlighted the fact that rural areas are more dependent on disability benefits than the metropolitan areas. This was according to an investigation of the rate of Social Security benefits received by working adults nationwide in 2009. To qualify for disability benefits, a person has to prove he/she cannot work because of a disability that will last more than a year. The particular disability will be determined via a comprehensive medical records review.

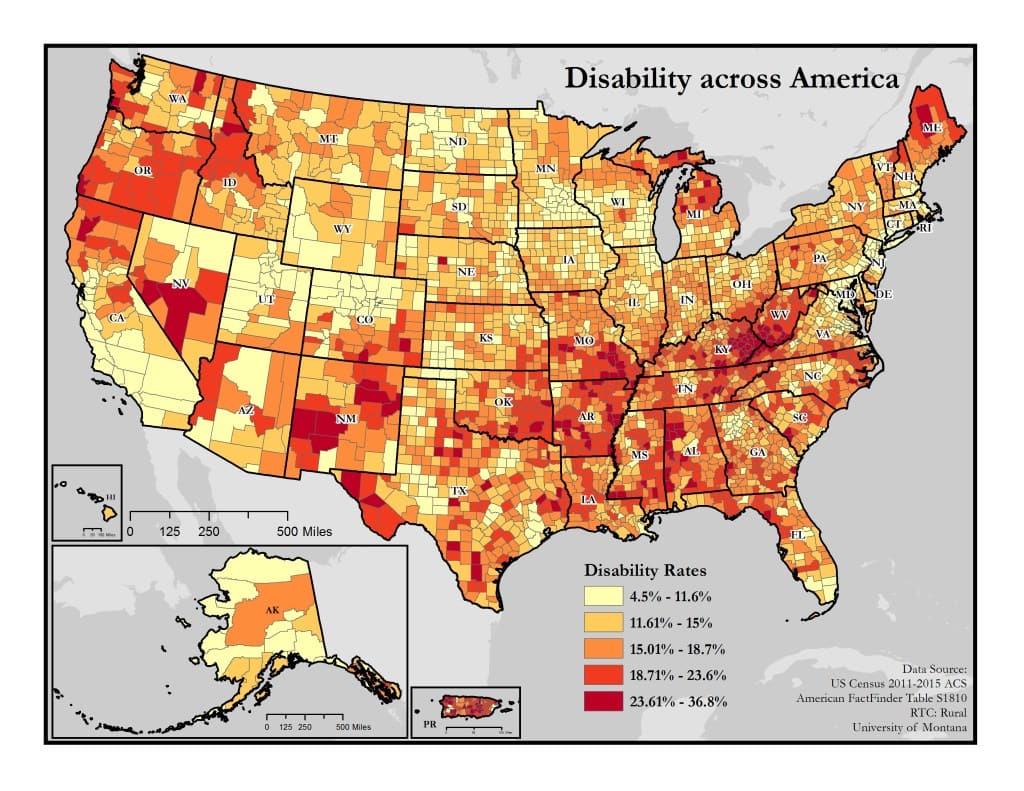

Disability is indeed a serious concern in rural America, as data from the American Community Survey, an annual government poll, shows. Disability is more common in rural counties than their urban counterparts. It was found that the rate of disability increases from 11.8% in the most urban metropolitan counties to 15.6% in smaller micropolitan areas, and 17.7% in the most rural/non-core counties. The poll data provides a picture of geographic variations in disability across the nation. Disability rates in rural America are not homogenous but range from around 15% in the Great Plains to 21% in the central South.

The investigators suggest that the regional and rural differences could be attributed to different factors such as difference in demographics, economic patterns, health and service access, and state disability policies. However, they also point out that there are limitations to the survey because the data does not measure disability directly since they only evaluate physical function and do not consider environmental factors such as inaccessible housing.

Terrence McCoy in his article in washingtonpost.com talks about disability benefit rates in the United States and points out that disability recipients are disproportionately prevalent in rural America, where 9.1% of the working age population receives disability compared to the national average of 6.5% and an urban rate of 4.9%. Economists have assigned the name “disability belts” to certain regions in the United States that are places where post-recession aging workers in poor health and with dim prospects for work have turned to federal disability benefits as a replacement for their lost wages. Rural areas in the Deep South, Appalachia and along the Arkansas-Missouri border form part of the disability belts. Bloomsberg provides statistics of the percentage of residents in these areas, age 18 to 64, receiving disability benefits:

- The county with the lowest rate of disability claims in the United States is Aleutians West, Alaska with 0.4%

- Lewis County, Idaho – 17.7%

- Floyd County, Kentucky – 17.5%

- Dickenson County, Virginia – 20.2%, the highest rate in the United States

- Van Buren County, Arkansas – 11.3%

- Mingo County, West Virginia – 16.7%

- Buchanan County, Virginia – 19.7%

Four of the five counties with the highest disability payout rates are in Appalachia. Economists believe that declining job prospects and an aging workforce rather than fraud are the reasons for the increase in disability claims across the country. In some rural areas, where aging, unskilled people with some disability or other can’t find work, social security beneficiaries are more. There is no recourse other than Social Security for workers in geographic regions with few job openings, low incomes, and limited purchasing power.

Researchers in the field believe that health outcomes differ across geographic regions, which may account for so much variation in disability rates across these regions. Other factors that contribute to this difference include geographic differences in behavior, genetics and healthcare.

- Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) takes into consideration health outcomes across geographic regions as well as the differences in economic conditions across these regions.

- When granting benefits, the SSA gives importance to economic factors because while workers with a disability are more likely to find employment in a geographic region with lots of job opportunities, disabled people will find it difficult to find work in a region with comparatively lesser jobs and where many of the jobs have fundamental manual requirements.

Vocational considerations or the worker’s other job prospects have been an important contributing factor in the increase in disability over time. Since economic criteria are a major consideration in the SSDI awards process, disability rates would be in proportion to the great disparities in job opportunities across counties. With economic divergence in various regions, the SSDI rates also vary partly because the benefit awards process takes into account the economic conditions the disability applicants face. In regions weighed down by relentless unemployment and poverty, disabled and desperate workers rely completely on Social Security benefits as a means of livelihood. Many of these people do not expect to return to work unless they are removed from the disability rolls by federal investigators.

Given that the Social Security benefits programs face an uncertain future, it is important that disabled workers are encouraged to return to work as soon as possible. SSDI was created for an economy wherein working was a profoundly physical activity. Today’s economy is service oriented wherein disabled people can still find jobs they can do and be encouraged to get some form of suitable employment. SSDI should be modified taking this into account and benefits should be provided to those people who truly cannot work, while encouraging others to do the jobs they can. As economists point out, disabled workers should be assisted to reach their employment potential or maintain economic self-sufficiency with medical advances and improved equipment available now. Workers with disabilities should not consider the program as an alternative to stay permanently out of the labor force.